Note: The Article copied from Blue Pyramid Egyptians before closed.

Archive Article #14 - 12/20/02

To understand a thing, the forces that shaped it must first be understood. Long before the Egyptians embraced the Arabian horse, the Bedouin of Arabia forged the animal into a distinct creature of unrivaled beauty, hardiness, and intelligence. Although the origins of the Arabian horse are marked by periods of uncertainty, there can be no doubt that it was through the husbandry of the nomadic tribes of the Arabian desert that the animal was carefully selected and bred for certain characteristics that suited the needs of the Bedouin.

Travelers to Arabia report in their journals of searching the vast deserts from the Red Sea to Iran and Syria on their quests for the purest and finest Arabian horses. Most of them came to the conclusion that the best horses came from the Najd, the heart of Arabia.

Not all Arabs were Bedouin and not all Bedouin were camel-raising nomads, but all could be classified as hierarchical tribal family units and all embraced the ghazu (raid) [1], as an honorable occupation. Some families grew very strong and claimed special fertile areas for their own that allowed to them to become more sedentary and, although still keeping to a tradition of raiding, these groups became town dwellers. Such were the people of the Al Sa’ud family that claimed Riyadh as the heart of their territory. The hills and area around Riyadh provided abundant year-round forage for raising their livestock and especially, to concentrate on the refinement and improvement of their horses. The story that follows is a brief look at the man that led the Al Sa’ud in their quest to take Riyadh at last and eventually control most of Arabia.

Out of Arabia

by Samantha Winburn

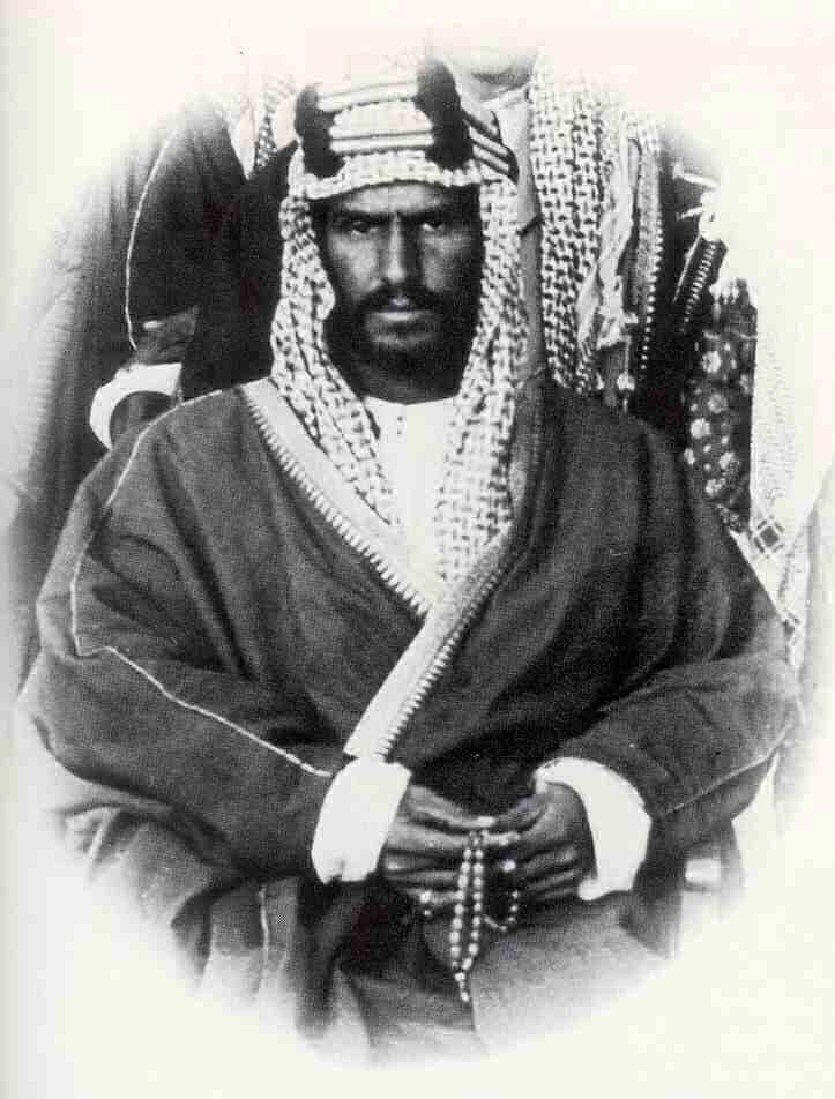

In 1891, for the second time, the rival Al Rasheed dynasty drove the Al Sa’ud out of Riyadh. The survivors led by Abdul Rahman Al Sa’ud, sought sanctuary with the Murrah Bedouin tribe, their allies on many ghazu. With the Al Sa’ud was Abdul Rahman’s son, the fifteen-year-old Abdul Aziz, who credited his years with the Murrah for forming the basis for all that he was. “The dreams of the boy as he slept on the sands of Arabia were of recapturing Riyadh, avenging his family’s honor, and sweeping across Arabia to recreate the empire of his forefathers.”[2]

|

Abdul Aziz Ibn Sa'ud |

In the mid-1890s, the Al Sa’ud moved to Kuwait. Their host, Sheikh Mubarak Al Sabah, was an ambitious man and under his tutelage, Abdul Aziz served his political apprenticeship. In 1901, the Al Rasheed marched from Riyadh to mount an attack on Kuwait. The British, fearing the alliance the Al Rasheed had formed with the Turks (and thus with the Germans), landed guns at Kuwait to protect the city from the landward side while their boats protected the ports. Learning of this, the Al Rasheed stopped short of Kuwait and withdrew north to Baghdad and their Turk allies. Mubarak supported Abdul Aziz’s plan to recapture Riyadh and it was at this time, with the Al Rasheed far to the North in Baghdad, that the young man took advantage of the their absence from the desert. With 40 companions, Abdul Aziz rode south along the Persian Gulf toward Riyadh, surviving by the ghazu. After months in the desert, Abdul Aziz and his followers, now grown to hundreds of men, lay outside Riyadh ready to retake the town. But Rasheed had heard of the plan and alerted his men in Riyadh who were ready for the attack. So Abdul Aziz took 60 of his most loyal followers and moved south and east from Riyadh into Murrah territory, the Empty Quarter, where they vanished from sight. For 50 days they rested and marshaled their strength until the garrison at Riyadh, believing the Al Sa’ud had abandoned their plans, relaxed their vigil. |

Early in January 1902, Abdul Aziz and his followers began to move in stealth back to Riyadh. They traveled by night until, on the last day of Ramadan, they lay in hiding on a plateau overlooking Riyadh. Throughout the day, the townspeople celebrated Eed al Fith, the end of Ramadan. At sunset, Abdul Aziz and 40 of his men crept to the edge of the walled city. Leaving most of his party hidden in a palm grove, Abdul Aziz took six men and, using the trunk of a palm tree, climbed the wall that surrounds Riyadh. They made their way through the sleeping town and gained access to the governor’s house that was directly across the square from Mismak Fort, the stronghold of the Al Rasheed garrison. Finding that the governor had spent the night in the fort, one of Abdul Aziz’s sentries returned to the palm grove and brought the rest of the group to the house. There they waited for the governor to appear. At first light, the governor left the fort by a small postern gate and started across the square toward his house. Abdul Aziz and his band rushed into the open square, chasing the governor and his guards through the postern gate and diving through the opening behind the fleeing men. Only the luck of the surprise attack kept them from being hacked to death as they entered the fort one by one. They killed the governor, took the garrison, and reclaimed the city. It was the third time the Al Sa’ud had taken Riyadh and this time it was for good and established their empire.

Abdul Aziz’s remarkable success was a magnet that drew people to him. By 1931 he had united all the sheikhdoms and sultanates of Arabia, established a governing body, and formed the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, making Riyadh the seat of the new government.

Abdul Aziz Ibn Sa’ud amassed much property and wealth as the leader of Saudi Arabia. One of his passions was the desert-bred horses he had come to know during his years with the Murrah. His march through Arabia to retake the tribal lands, and his liaisons with the Ruala and Anazeh through his wives gave him access to the finest horses in the desert. The Al Sa’ud had a long history of breeding the finest Arabian horses in the Najd (the area around Riyadh, famous for its horses). During an earlier Al Sa’ud reign, Arabian horses from the family’s stud farm in Dar’iyah had been taken by Ibrahim Pasha who, on behalf of the Turks, led the 1881 campaign to push the Al Sa’ud out of Arabia. The siege at Dar’iyah lasted six months, was cruel and bloody, and left nothing but a ghost town. Now back in control of Riyadh and the surrounding area, Abdul Aziz Ibn Sa’ud and his sons established a number of stud farms in Riyadh, Al Khormah, and other locations in the growing territory of the reestablished Saudi Arabian empire.

|

The Royal Gift of Horses In 1945, Abdul Aziz made a gift to Egypt's King Farouk of the Saqlawi mares Hind and Mabrouka and the Kuhaylan mare Nafa'a. These mares were incorporated into the Inshass Stud that Kings Farouk and Faoud of Egypt (combined rule: 1917-1952) maintained as their private venture (ironically, it was Dr. Mohammed Rasheed who managed Inshass at that time). Most of the Inshass breeding stock came from established Egypt I and Egypt II bloodlines, but the kings also acquired other foundation horses for racing and/or breeding or received them as gifts, such as the three mares from the Sa’ud family of Saudi Arabia. The 1952 revolution swept Farouk out of power. The revolutionary government took over the king’s holdings and Inshass became, and remains, an army base. The army kept some of the horses and continued breeding them, but eventually the balance of Inshass horses were transferred to the Egyptian Agricultural Organization (EAO). Some were sold and the remainder went to the stud farm at El Zahraa. |

|

One of the three mares sent to Egypt by Abdul Aziz, was the Kuhaylan mare, Nafa’a (Obeyan el Siefi x a Keheila mare), who was foaled February 1, 1941[3]. While at Inshass, Nafa’a produced four foals: Nadia (x Ezzat), a 1947 mare [4]; Nafei (x Hamdan), a 1949 stallion [5]; Nadi (x El Balbesi), a 1950 stallion [6]; and Nadir (x Hamdan), a 1952 stallion [7]. In 1953, Amad Hamza purchased Nafa’a from the Egyptian Police for the Hamdan Stud. While at Hamdan, Nafa’a produced an unnamed filly (x El Fol) that died soon after birth then in 1962, the mare Bint Nafa’a (x el Gadaa) who in 1968 produced the mare Negma Dawliyah (x Fol Yasmeen).

|

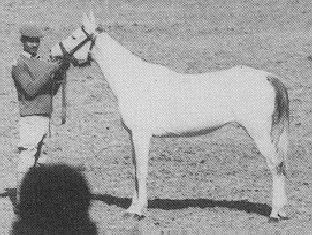

Serenity Bint Nadia (Photo by Judith Forbis) |

The only Nafa’a daughter with straight Egyptian/Al Khams (SE/AK) progeny was Nadia (1947) who was sold to the Kobba Stables in 1950 where she produced Bint Nadia (x Sameh) in 1960. Shown here is the only known picture of the Nafa’a granddaughter, Bint Nadia (Sameh x Nadia); Judith Forbis took the photo at the Egyptian Police Academy. In 1970, Doug Marshall, on a buying trip to Egypt, saw the mare and purchased her for Hansi Heck-Melnyk. Hansi imported Bint Nadia to Canada and registered her as Serenity Bint Nadia. It is probable that Serenity Bint Nadia is the only Nafa’a descendant with surviving offspring.

|

Serenity Kamila produced the stallion SF Untouchable (by *SF Ibn Nazeer) for Serenity Farms then was sold to Imperial Egyptian Stud where she produced IES Kameesha (by Hossny) in 1978. She produced IES Kaamelah (by Hossny) in 1979. Serenity Kamila was sold to Count Federico Zichy-Thyssen and exported to Argentina in 1979 where she was bred repeatedly to Hossny and produced ZT Hossinette in 1980, ZT Bint Hossny in 1981, and the stallion ZT El Hadidi in 1982. She returned to North America in 1982 where she produced VA Shah Farouk (by Ansata Shah Zaman) in 1983. Serenity Kamila died the following year. |

Cedardell Tiffany was bred exclusively to Dalul and produced the mare Diaa in 1980, the stallion Dal Keraim in 1981, the mare Keraima in 1983, the stallion Drakkar in 1984, the mare Dahleeah in 1985, and the mare Delha in 1986. Of her offspring, only Drakkar and Delha remained in the United States, the others were exported to Canada.

|

Bt Kameesha Amira |

In addition to the Blue Pyramid Egyptian mares, including the 2008 filly Bint Kameesha Amira, the Nafa'a AK/SE female descendents of breeding age (<20years) are Bint Drakkar (Drakkar x Le Kameesha Amira), Extremely Nice and her daughter JF Kameerah owned by Midnightsun Arabians, all representing Serenity Kamila. There are only Last Chance Too, JF Amir Ibn Kameerah (2007), and JF Extreem Chance (2008) to carry the Serenity Kamila line on top. The three AK/SE Cedardell Tiffany stallions in the US are El Norus (book closed), Ibn El Norus, and Drakkar (retired). Add to that the rarity of the Kuhaylan-ns strain and from any standpoint, the Nafa’a line is one of the rarest straight Egyptian Al Khamsa lines in the world today. |

Extremely Nice |

The loss of San Emira Farazdac represented a great blow to the Nafa'a preservation program. But our hopes for the Serenity Kamila line were renewed the birth of Bint Kameesha Amira and the purchase of JF Amir Ibn Kameerah. Amir is the first double Serenity Kamila foal and will be bred to Bint Kameesha Amira when she is of age.

|

El Norus |

Last Chance Too |

JF Amir Ibn Kameerah |

Ibn Norus |

Nafa’a was the only horse listed as Kuhaylan with no substrain (Kuhaylan-ns) in the EAO studbooks volumes III and IV, the original Raswan Index, and the Manual of Straight Egyptian Horses. Some believe that another mare, El Samraa, may also be Kuhaylan-ns, but it is generally accepted that she was Saqlawi. El Samraa has many offspring, but even taking into account her numerous progeny, the Kuhaylan-ns strain must be considered one of the rarest in existence today. The lack of horses, the distances that separate them, and today’s economy has made the preservation of these horses a great challenge, but the results exceed expectations.

|

|

|

Dahloura |

Shaloura |

|

||

San Baazinah |

Le Kameesha Amira |

San Aakefaa |

There may be SE/AK Nafa'a daughters somewhere that were never registered so have effectively been lost to the gene pool. At this writing and with the loss of San Emira Farazdac, the AHA database shows 57 Nafa’a offspring registered in North America. People seldom notify the registry when a horse passes away so there may be some that are alive but, because they are not in production or have no registered offspring, cannot be counted as viable in preserving the bloodline. They are therefore not considered “living offspring” in the sense that they are likely to continue the line. In this way, entire bloodlines are lost and the Nafa’a line is dreadfully close to slipping into extinction.

|

|

bpe Shah Hilala |

San Emira Farazdac |

The late Al Khamsa advocate Carol Lyons once challenged concerned breeders to step forward and embrace the rare bloodlines. The straight Egyptian Al Khamsa line is rare among Arabian horses and within that group, is the unique blood of Nafa'a. It is imperative that these rare and beautiful horses be bred to concentrate and preserve the precious blood of Nafa’a so that the mare line and indeed, the rare strain of Kuhaylan-ns does not become extinct and disappear forever.